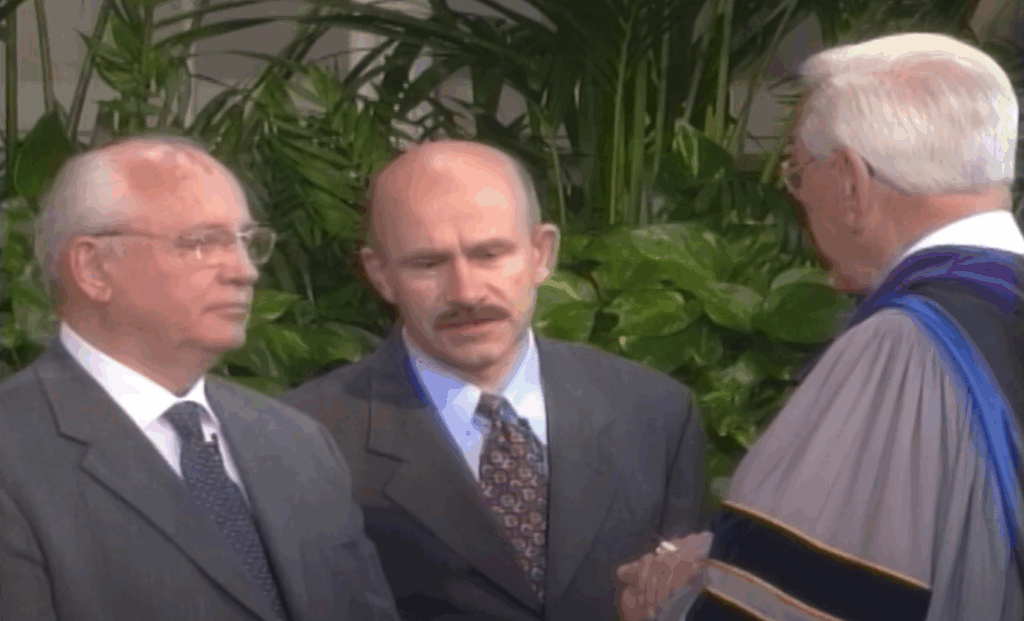

For people familiar with American religious history of the late 20th and early 21st centuries and the ubiquity of televangelists, the mise en scène in one particularly famous megachurch looked tried, true, and familiar. The music and the choir slowly fade out in the background while another camera, with the same deliberate speed, steps in to present into the foreground the reverend protagonist and his (it was usually his) VIP guest or the minister du jour. The church is the Crystal Cathedral in Garden Grove, California. The year, 2000. The minister, donning his iconic gown, is Robert Schuller. His VIP being none other than Mikhail Gorbachev, the late president of the late Soviet Union.

Schuller, who was no stranger to celebrity and counted many of them among his friends ranging from John Wayne to Evel Knievel to Frank Sinatra, was clearly pleased to host Gorbachev, a professed atheist and a former leader of an officially atheist former superpower.

Introducing Gorbachev to a capacity crowd, Schuller recounted the start of a “wonderful relationship with a man that I respect I think as much as I would Abraham Lincoln if I had lived in his day.” Schuller then went on to note that “there is no doubt that no one person brought an end to the Cold War like Gorbachev. And we had to celebrate our anniversary year by having this man come here so we can thank him for the faith that is now reaching millions and millions in his country. The Cold War was still on in 1989. And the Berlin Wall was still there. And when he put me on television, I was an enemy.” Schuller then takes a pause allowing the translator to convey to Gorbachev what had been said. The camera slowly zooms in on Gorbachev who is seen nodding in agreement and then lets out a surprised, if wry, smile after the translation of the word “enemy” has landed. Gorbachev then moves towards Schuller who embraces his old “enemy” (and new friend) while exchanging kisses on the cheeks to a standing ovation. A more dramatic, almost Shakespearean, irony could not have been imagined. A witness to this amiable episode between two unlikely and friendly dramatis personae could not be faulted for thinking that she was living in the era of plowhshares made from weapons, as the ancient Hebrew prophet Isaiah had envisioned. We were at the end of history, to steal from Francis Fukuyama, or at least nearing it.

But even more dramatic than Schuller’s introduction were the words spoken by Gorbachev himself, at one point declaring that “the revival of the Russian Orthodox Church is one of the most important gains of perestroika.” Reminiscing about his late mother’s support of him during one of the hardest periods of his rule, the 1991 failed coup d’état, the teary-eyed Gorbachev went on to declare that his entire family had been Christians for generations: “My entire family consisted of believers. … Our rooms were adorned with icons. My grandmother was always praying. And the most interesting part perhaps was the fact that right near those icons there was also a little table on which my grandfather kept portraits of Lenin and Stalin.” For scholars of the Cold War and Soviet history, Gorbachev’s appearance alongside a religious leader let alone an American one would be from the realm of fantasy just a decade before.

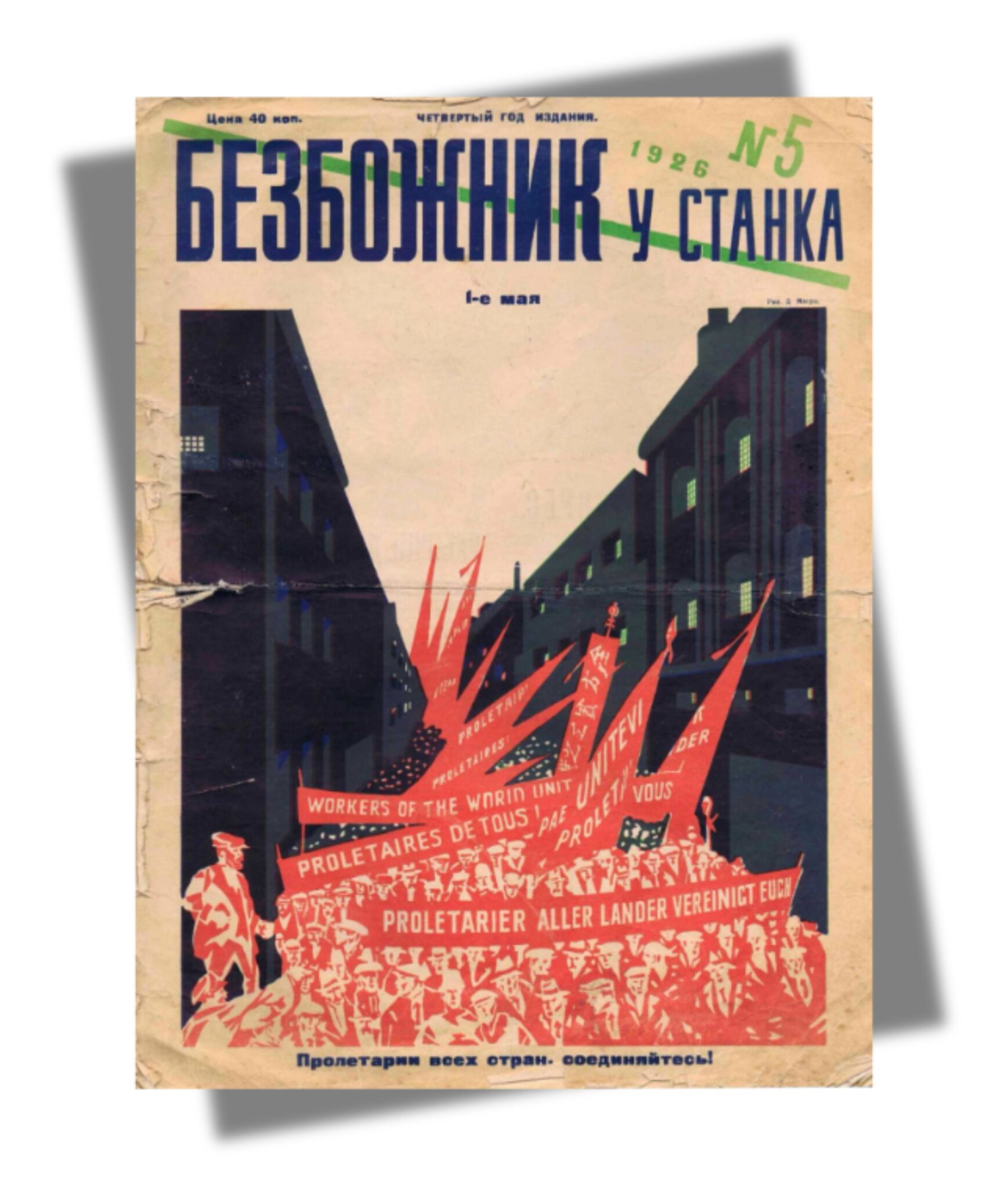

Nevertheless, Gorbachev’s “sermon” was indeed a dramatic departure from his professed atheism and the militant secularism of the Soviet state he once presided over. Lest we forget, it was the Soviet Union that gave us the League of Militant Atheists, the publisher of Bezbozhnik, the flagship atheistic propaganda publication ceaselessly and venomously ridiculing religion and clerics, all in the “interests of our communist education, our cultural socialist construction,”1 as Boris Kandidov, one of the Soviet Union’s most prominent propagandists of atheism, had put it.

It would be an exercise in futility to look for some sort of profound insight from a private citizen’s appearance in a church an ocean away while on a public speaking tour. It would be even more so to assign it some grand political significance. Nevertheless, Gorbachev’s appearance at the Crystal Cathedral cannot be dismissed out of hand either if only because it was a solid indicator of the changing perception of public religiosity by former and current officials in Russia.

Materials cited in this post are courtesy of Izvestiia Digital Archive and Soviet Anti-Religious Propaganda e-book collection, both of which are available through East View Information Services.

NOTES

- Boris Kandidov, Legenda o Khriste v klassovoi bor’be (The legend about Christ in class struggle), (Moscow: Ateist, 1930), 82. ↩︎