“People ask me: “Why don’t you take photos in color? In color!” But Chernobyl: literally it means black event. There are no other colors there.”

― Svetlana Alexievich, Voices from Chernobyl: The Oral History of a Nuclear Disaster

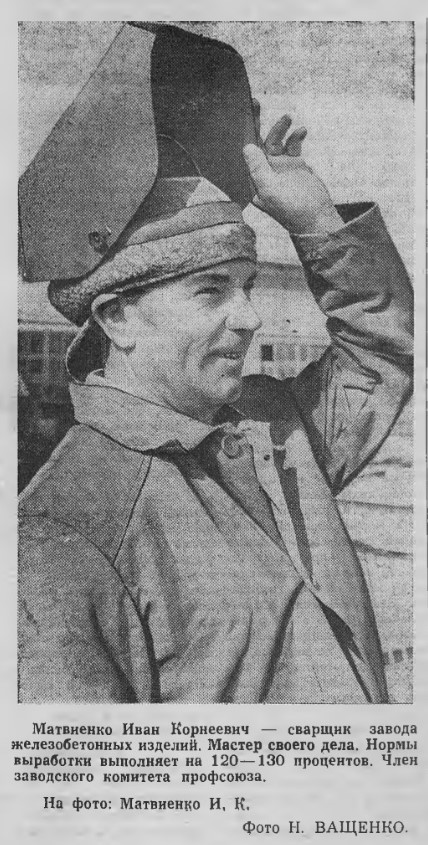

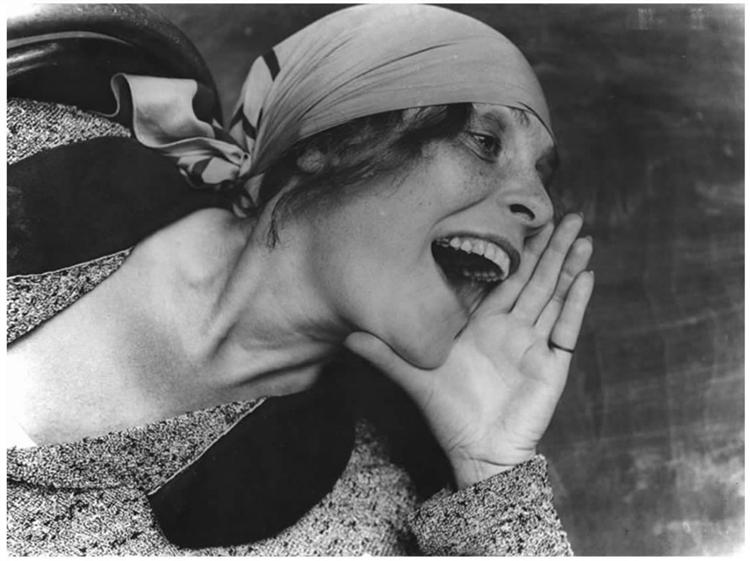

The front page of the inaugurating issue of Tribuna Energetika (Energy Worker’s Tribune), announcing the publication of the newspaper and its lofty mission, features a black-and-white photograph of a welder who has just lifted his mask and is looking as if into the future with what appears to be a genuinely warm grin. There are a couple of reasons why the image is arresting, despite its bland aesthetics and rather mediocre artistic merit. It is not in the same league as, say, the iconic portrait of the ebullient Lilya Brik by Alexander Rodchenko, shouting with a cupped hand towards the invisible masses. It lacks Rodchenko’s compositional dynamism and “meme potential,” and yet, despite all that, it gets the job done all the same. Insofar as it was meant to convey the ‘exuberance’ of the builders of communism, it certainly did so.

Even in the grimmest of circumstances, a grin from a fellow human, whether genuine or feigned, can elicit positive emotions. My son, at a tender ten years of age, is particularly well-versed in manipulating this basic, and by all accounts overpowering, human urge to answer a smile with a smile. He knows well that when he has misbehaved and is about to invite my loving disapproval, all he must do is smile, knowing full well that, like a Pavlovian canine at the ring of a bell, I am conditioned to smile back. Smile means mitigation. Smile means an averted punishment. Then comes the hug, then the rinse, then the repeat. Maybe I am gullible, particularly when it comes to smiling counterparts. It is a trap, however, that I walk into every single time. It also happens to work for propaganda purposes. And none were privy to this psychological perspicacity more than Soviet propagandists. They not only manipulated images, they manipulated with images.

A second reason why the photo is arresting is because of what was to come 17 years after it was taken. We don’t know whether the smiling subject of the photo was alive and well at the time of the Chernobyl disaster and still lived in his flat in Pripyat. But this lack of knowledge does not take away from the uncanniness of the photograph. Here’s a smiling worker, who was building communism by building a nuclear reactor. Knowing what we know now, was this worker also an unwitting gravedigger, building a future gravesite? Perhaps even his own?

This tension between hope and tragedy is further exemplified on the pages of Tribuna Energetika in a poem penned by another resident of Pripyat, N. Shakura, whose poem Peaceful Atom contained following lines

…

We move forward, meter by meter.

Neither heat, nor rain, or frost, and wind

can restrain our striving!

We believe, we know: the atom

will serve people for peaceful purposes

and will strengthen the Motherland.

The real irony of course lies in the fact that far from strengthening the erstwhile motherland Chernobyl’s “peaceful atom” would accelerate its demise. As Mikhail Gorbachev would put it 20 years later, “The nuclear meltdown at Chernobyl …, even more than my launch of perestroika, was perhaps the real cause of the collapse of the Soviet Union five years later. Indeed, the Chernobyl catastrophe was an historic turning point: there was the era before the disaster, and there is the very different era that has followed.”

Some of the materials in this post are found in Chernobyl Newspapers Collection and are available through East View Information Services.