Question to Radio Armenia:

“Is it possible to build Communism in a randomly taken capitalist country, for example, Holland?”

Answer:

“It’s possible, but what did Holland ever do to you?”

In his bilingual compendium of Soviet underground jokes Forbidden Laughter, Emil Draitser makes the pointed, if ironic, observation that “The anecdote in the Soviet Union substitutes for lots of expensive medication. It heals bleeding spiritual wounds, eases nervous tension, and lowers high blood pressure.”1 In that regard, the medicinal and curative aspects of Soviet jokes and humor were no different from their capitalist counterparts, albeit the malaise of the “Soviet soul,” (insofar as it was a thing), was qualitatively different from the one gripping souls under capitalism. But I suspect that is not what Dreitser had in mind when he made his observation. Rather, to Dreitser and many others, Soviet-era jokes, both underground and over the counter, were seen as a coping mechanism in a society devoid of the Marxian “opium of the people” (i.e. religion),2 that other famous social crutch that allowed otherwise limping walkers to straighten their posture and strengthen their gait.

Be that as it may, in the Soviet Union, jokes were more than jokes and served a variety of social functions (in addition to psychological ones), especially when laden with political content and political intent. It is this social and political dimension of jokes and their subversive potential that George Orwell had in mind when he famously wrote that “every joke is a tiny revolution.”3 Told and retold in hush-hush tones and behind doors under seven locks, these jokes, or анекдоты (anecdotes), had the power to erode and upend the existing social and political order, much like a small fire could undo a castle. It is thus no wonder that totalitarian regimes like the Soviet Union have always tried to control what people thought by trying to control (rather unsuccessfully) what they laughed about. In this regard, these jokes were also a folkloristic and anthropological barometer, measuring and reflecting the social mood. No wonder they also presented a potent, ground-level research environment for intelligence services and foreign diplomats trying to understand social currents in closed societies in the absence of more formal mechanisms like public surveys.

“The anecdote in the Soviet Union substitutes for lots of expensive medication. It heals bleeding spiritual wounds, eases nervous tension, and lowers high blood pressure.”

Emil Draitser, Forbidden Laughter: Soviet Underground Jokes

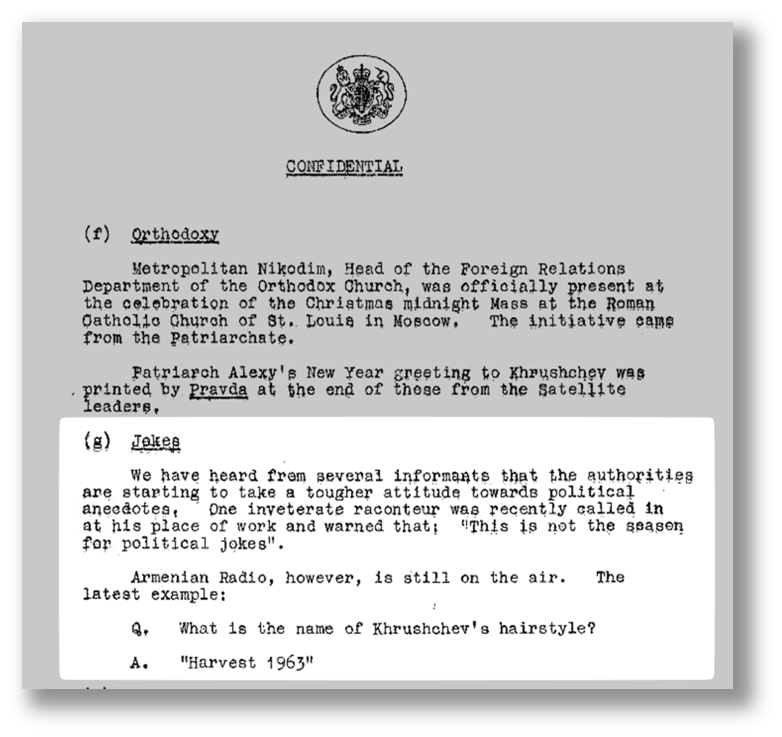

An illustrative case in point is to be found in the dispatches by British diplomats stationed in Moscow at the height of the Cold War. These dispatches, available through East View’s Archive Editions, provide a unique glimpse into the issue. In a 1964 confidential dispatch, for instance, an unnamed British diplomat writing to his or her superiors in the Foreign Office made sure to note that “We have heard from several informants that the authorities are starting to take a tougher attitude towards political anecdotes. One inveterate raconteur was called in at his place of work and warned that: ‘This is not a season for political jokes.’” The writer then would go on to continue the dispatch by cheekily noting that Armenian Radio was still in business, cracking jokes at the expense of the Soviet leadership and making fun of the recently deposed Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev’s bald cranium.

In conclusion, Soviet-era humor was more than met the eye. It was meant to be amusing, to be sure, but also served as a vital mechanism for social and psychological survival. And insofar as it had political content, it was a subtle form of rebellion against a repressive and fundamentally mirthless regime. The irony, as British dispatches reveal, was that no matter how hard authorities sought to clamp down on “unauthorized” humor, the unnamed Soviet “raconteurs” and “tiny revolutionaries” kept defying the regime through wit and laughter.

The materials in this post are found in East View’s Soviet Union Political Reports, 1917–1970 via the Archive Editions, the vast collection of British archival documents, now fully digitized.

NOTES

- Emil Draitser, ed., Forbidden Laughter: Soviet Underground Jokes (Los Angeles: Almanac Press, 1978), 3. ↩︎

- Karl Marx, A Contribution to the Critique of Hegel’s Philosophy of Right, https://www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/1843/critique-hpr/intro.htm ↩︎

- Sonia Orwell and Ian Angus, eds., The Collected Essays, Journalism and Letters of George Orwell, vol. 3 (London: Secker & Warburg, 1968), 284. ↩︎