Anyone familiar with literary devices employed by writers to propel narratives forward must at one point or another have come across one such famous device known as “Chekhov’s gun.” Named after the famed Russian writer and playwright Anton Chekhov, who first theorized about the device in a letter to fellow Russian belletrist Aleksandr Lazarev, the principle posits that unless a gun is intended to go off at some point in a play, it should not be introduced at all.

A hallmark of good storytelling is the coherence of its elements, each narrative component working both independently and in concert to guide the plot from exposition to resolution. Thus, a gun that fails to go off is as good, or as useless, as a broken compass on a hike through a treacherous terrain. As Chekhov himself put it, “one should not make promises (in a play) if one has no intention of keeping them.” In other words, one cannot violate the expectations of the audience unless upending those expectations is the point being made.

Little did the trio of Leonard Bernstein, Arthur Laurents, and Stephen Sondheim imagine that when they put the gun in Chino’s hand in New York to kill Tony in West Side Story, it would fail to serve its intended purpose thousands of miles away in Yerevan, the capital of Soviet Armenia, in 1963.

But first things first.

A New Year’s Eve 1964 article on page 11 of The New York Times ran with the curious title “West Side Story is Staged in Soviet.” Interestingly, the Times’ framing of the story was not centered so much on the staging of the Broadway hit as an important cultural milestone in the USSR, (surely a quintessential Broadway work on a Soviet stage would have qualified), but rather as yet another case of intellectual property theft, which it certainly was.

“The Soviet Union,” the article observed dryly, “reached another free hand into Broadway’s musical repertory tonight and came up with West Side Story.” It went on to note that “Soviet authorities refuse to pay royalties for [the] production.” It was, perhaps, one of the clearest and, dare we say, most theatrical cases of disregard for intellectual property rights since the Lacy–Zarubin Agreement on cultural exchange between the U.S. and the USSR, signed in 1958. Lenin had decades earlier declared that “art belongs to the people,” and so it was. Or so went the logic behind the Soviet refusal to pony up or plunk down.

Even more interestingly, however, it was not the first time that West Side Story had been staged in the Soviet Union. As it turns out, that honor goes to the performers of the Alexander Spendiaryan Opera and Ballet Theater Company in the Soviet Armenian capital of Yerevan. This unauthorized staging, however, went largely unnoticed in the West and barely registered in the Soviet press, with the exception of a few brief mentions in the Armenian press, such as in the magazine Sovetakan Arvest (Soviet Art) and the flagship party organ Sovetakan Hayastan.

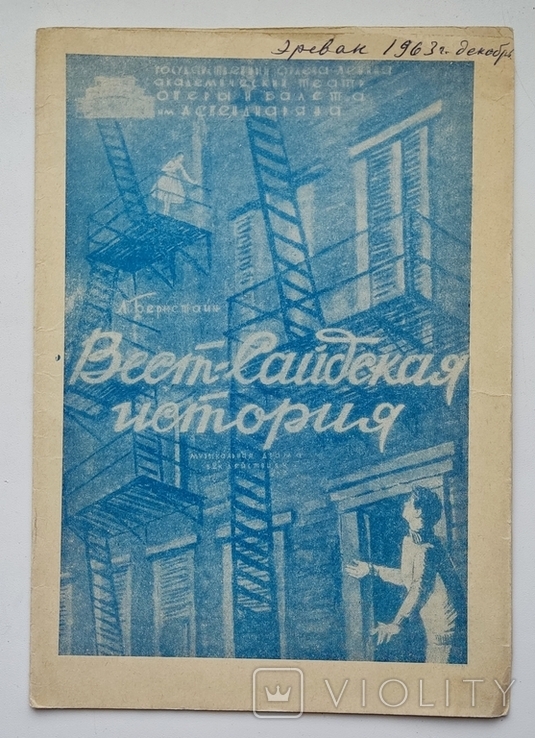

Meanwhile, the program booklet, an ephemeral souvenir of the production, survives today only in an obscure online auction listing in Poland.

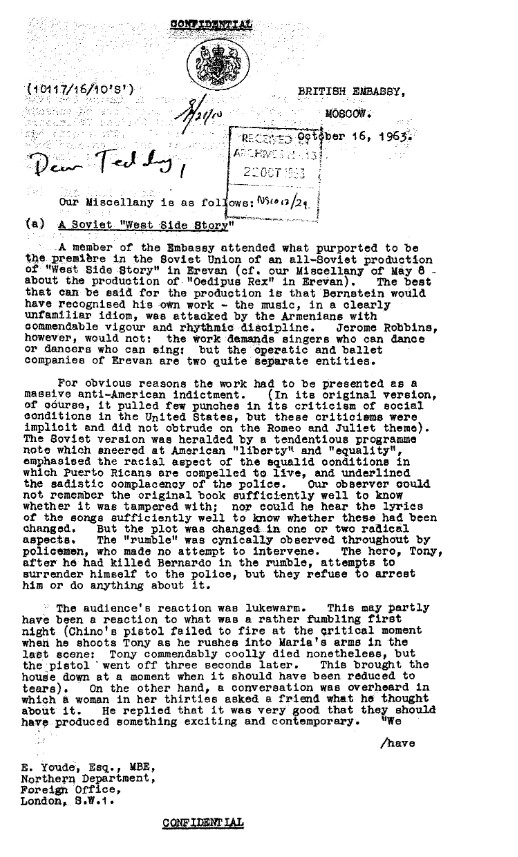

We learn about the staging through a brief, five-sentence report in the American trade magazine Variety from October 1963, titled “An Armenian Ballet to Tour Soviet; Inspired by West Side Story.” A more substantial testimony survives in the form of British diplomatic cables.

It remains unclear why a Moscow-based diplomat would travel to the Soviet periphery to attend a musical production and write up a report. But if we are to speculate, then an article published in the Armenian newspaper may offer a plausible clue: the presence in the audience of Anton Kochinyan, Chairman of the Armenian Council of Ministers.

According to the unnamed British diplomat who attended the premiere, “Bernstein would have recognized his own work, the music, in a clearly unfamiliar idiom, was attacked by the Armenians with commendable vigour and rhythmic discipline. Jerome Robbins,1 however, would not: the work demands singers who can dance or dancers who can sing, but the operatic and ballet companies of Erevan (sic) are two quite separate entities.” In other words, there were singers who could sing but not dance, and dancers who could dance but not sing.

The diplomat further noted that “for obvious reasons the work had to be presented as a massive anti-American indictment.” That feat was achieved in no small measure through the “radical” liberties taken by the producers. His (or her) assessment was echoed in a review that appeared in Sovetakan Hayastan under the title “Story About Concrete Jungles.”2 According to that review, the “story is about the American youth, the same youth which is devoid of high ideals, true calling, which does not know where and how to expend its passion and its strength, and is confused in the tangles of racist prejudices. In short, it is a story about New York’s concrete jungles.”

Unlike the anonymous British diplomat, who found the audience’s reaction lukewarm, the Armenian reviewer stressed that the premiere was a resounding success, and was received warmly by art lovers.

And then, of course, there was the matter of Chino’s gun.

At the beginning, Chekhov’s gun in Chino’s hand was invoked. It would be remiss not to have him fire it if we are to stay true to Sondheim’s libretto and Chekhov’s axiom. According to our anonymous diplomat, “Chino’s pistol failed to fire at the critical moment when he shoots Tony as he rushes into Maria’s arms in the last scene: Tony commendably coolly died nonetheless, but the pistol went off three seconds later.”

Chekhov would have appreciated the irony.

Some of the materials in this post are found in East View’s Soviet Union Political Reports, 1917–1970 via the Archive Editions, the vast collection of British archival documents, now fully digitized.